|

"Nazeing Glass and Its Origins"

An exhibition of Nazeing Glass was held at Lowewood Museum, High St, Hoddesdon from July

to September 2003, at which a wide variety of decorative coloured glass was on show, notably from the few years of pre, and

post war production of vases, bowls, lamps, and paperweights, along with drinking glasses that heralded a change in course

for the company.

The exhibition displayed the extent

of Nazeing Glass production, from its origins in the 1890's as producers of fine decorative glass, under the name of Kempton,

through to the specialist industrial pieces that they now produce. For example, a glass optical device made by Nazeing Glass

which was fitted in Challenger Tanks through to lighting lenses for railway and airport use.

The occasion was used to celebrate

the 75 years that glass has been made at the "Goats Shed" site on the Broxbourne/ Nazeing border. In 1928 the company

now known as Nazeing Glass moved from Southwark, London to the 'Goats Shed' site. The company logo still incorporates

a pair of goats, referring back to its origins, although the original structure has long since vanished.

In 1942 ownership of Nazeing Glass passed from the Kempton family into the hands of

the current owners, the Pollock-Hill family, when Malcolm Pollock-Hill, a former shareholder, purchased the company. Nazeing

Glass is now the last family owned commercial glass company in England.

__________________________

"Art Deco to Post Modernism - a Legacy of British Art Deco Glass"

A selling exhibition held jointly by Nigel Benson and Jeanette

Hayhurst at the Richard Dennis Gallery, Kensington Church Street, London, in Seprember 2003, which explored the manufacture

and design of cut glass in Britain from the 1920's to the 1970's, looking at the designs produced during this period

by both the lesser-known and previously unknown designers.

British glass manufacturers had maintained that it was traditional that sold during

the 1920's and 1930's and had largely ignored the Scandinavian approach where factories generally employed trained

in-house designers. There were exceptions to this, such as Keith Murray an architect who freelanced for Stevens & Williams.

Clyne Farquharson of John Walsh Walsh and William Wilson at Whitefriars were successful in-house designers and, as such are

highly regarded by today's collectors, along with the work of Keith Murray. These three designers are generally thought

of in connection with British glass design between the wars.

There is also an awareness of Ludwig Kny and perhaps of Reginald Williams-Thomas, but only a minority will know of J.Cuneen,

Freda Coleborn, Deanne Meanley, Doreen Norgrove, R. Pierce, or W. J. Whitworth, to name only a few. Not

many will have even heard of some of the major designers who influenced both contemporary and future generations of glass

designers, such as David Hammond, John Luxton, Helen Monroe, and Irene Stevens. On the other hand many collectors will know

the work of Geoffrey Baxter for Whitefriars, but it is only fairly recently that they have shown interest in his cut glass

work.

The most important events to affect British cut glass of the pre-war era were the exhibition "Modern Art for the Table"

held at Harrods in 1934 followed by "Art in Industry" held at the Royal Academy, in 1935. The Harrods Exhibition

saw a group of artists invited to submit designs to be produced both in ceramic and in glass. The glass was to be made by

Stuart & Sons and artists included Paul Nash, Graham Sutherland, Laura Knight, Eric Ravilious, Gordon Forsyth, Ernest

and Dod Procter as well as Stuart's Chief Designer, Ludwig Kny. Whilst the designs were critically acclaimed the buyers

were less enthusiastic, preferring the traditional designs that were tried and tested, and apparently sold well, however the

influence of these works is undeniable.

During the Post-war period British design was in a state of flux, designers looking to the future, manufacturers mainly

looking backward and depending on the work of yesteryear. The Government advocated the use of modern design and encouraged,

or sponsored, a number of exhibitions, beginning with "Britain Can Make It" in 1946 and culminating in the "Festival

of Britain" in 1951. Whereas nowadays we take for granted simple forms with, or without, restrained decoration, regarding

them as the norm, fifty years ago this was certainly not the case.

The work of both Scandinavian and Italian glass designers was evolving into a new stylish,

simple, organic form, and was also capturing the imagination of the British public. Magazines and papers were praising the

Scandinavian wares in particular and it was notable that British manufacturers were complaining about this trend in the pages

of such journals as the "Pottery and Glass Trades Gazette" and in "Pottery and Glass". Although it was

observed that North America imported large quantities of foreign glass of which British glass formed a large part. The complexities

of the need to export, combined with a wish to sell in the internal market, along with the need to look forward within the

post-war climate of austerity, produced a strange mix of traditional and modern design.

British glass companies had entered into the idea of employing fulltime-trained designers,

but these talented designers were compromised by their masters who still dared not go down the modern route. Occasionally

stylish, restrained work was produced, yet it is evident from contemporary catalogues that the majority of work produced was

of the traditional variety. Eventually tradition won and subsequently the major

British glass manufacturers were all to become defunct. Whether or not it was their inability to believe in modern design

as the way forward as being the main contributor to this sad situation is a matter for conjecture, but it has certainly proved

to be the case in other industries that are no longer with us.

Ironically, now is the time that much of the work

of these designers could have been appreciated. The success of a range of wares by John Rocha, introduced by Waterford in

the 1990's; the designs of John Luxton that were reprised in the late 1990's, bringing him out of retirement to develop

the ranges, and the addition of ranges designed by Jasper Conran before the demise of Stuart & Sons; and a range of wares

from Edinburgh & Leith, all proved highly saleable, and seems to make the point admirably, especially since the work either

echoes, or is a development of, work from both the 1930's and the 1950's. It also serves to illustrate just how far

ahead of their time the designs of these periods really were.

© Nigel Benson, September 2003

__________________________

"British 'Art' Cut Glass 1920-1970: A Fresh Look"

20th Century Glass was asked to hold a reprise of the exhibition "Art Deco to Post Modernism" by

the organisers of the NEC “Antiques for Everyone”. Held between 27-30 July 2006, the exhibition took

a fresh view of what has been termed British Art Cut glass (designer glass) under a number of categories, and, unlike

the previous selling exhibition held by Nigel Benson in conjunction with Jeanette Hayhurst in 2003 it, concentrated its attention

on the types of design on the glass rather that on its manufacture or history. Moreover, this exhibition included the

work of the designers Keith Murray and Clyne Farquharson in order to explore the subject in its fullest context.

Whilst the

history of an item is highly important in order to put it into context it often clouds the viewer’s overall impression

and ability to judge the glass on its own merits. Therefore, the purpose of trying to categorise items was to centre attention

upon the glass, whilst at the same time illustrating the similarities and differences between factories and designers.

For far too long this branch of British decorative art has suffered

from a lack of understanding and even descent, which in all probability is mainly due to the mistaken belief that it is all

so multi-cut with criss-cross lines that very little of the original surface is left untouched by the cutter’s wheel

and is therefore counter to the modern taste. This is largely an unfortunate legacy from the Victorian era when flamboyance

and over ostentation seemed to be the credo associated with design.

Georgian cutting, however,

was far more sympathetic to the vessel it was decorating and had a restraint that has become classic. Here is the link to

the twentieth century, its cutting and its designs. Indeed many of the designers of the post-war period were influenced by

Georgian cut glass – a tendency toward simplicity.

Designers have to consider what the inspiration for the design

is going to be and how that inspiration is going to be interpreted. Is it going to be a straightforward geometric pattern,

is it figurative, is it to be abstract, or indeed abstracted? An abstract design can be something that relies on a number

of things that will result in a non-representational motif, whereas if it an image is abstracted then it will be something

that is based upon a tangible item, such as a leaf, tree, animal, fish or even the human figure. Further, can the vessel in

question and its decoration be considered as sculptural? It

is therefore possible to categorise British cut glass of the twentieth century under a number of headings. Those headings

can themselves be subdivided. The exhibition used five different categories, Geometric, Figurative, Abstracted, Abstract and

Sculptural.

Largely speaking they are self explanatory, Geometric being repeated regular designs that can be simple or can become quite complex in their interpretation,

especially if a number of geometric devices are used in conjunction with each other. By contrast Figurative cutting relies on motifs derived from flora and fauna. Abstracted

motifs are those that relate to their inspiration, which is most usually flora and fauna, including the human form. Abstract is neither geometric, nor figurative and therefore has its origins entirely

in the mind of the designer. Lastly, there is the Sculptural, which, although

cut with a pattern relies heavily upon the form of the vessel that the cutting is on, or else the cutting creates that form.

This attempt to categorise cut glass design was to help the

uninitiated gain an understanding of the subject whilst allowing those with knowledge a greater insight. In addition to breaking

the subject into categories there was an opportunity to compare related designs produced by one factory with another. For

instance was horizontal wavy mitre cutting the sole province of one company, or was it used by a number of firms? If more

than one how is the device used? Is it deeply cut, or shallow? Or, are the lines used in conjunction with some other motif?

Since the exhibition there have been many favourable reports about how effective it was in answering the questions

it posed giving a greater understanding and accessibility to the subject of British Art Cut Glass to those who had the

chance to view it.

__________________________ "Pride

of Place"

In December 2007 the organisers of the Art Glass Fair asked 20th Centruy Glass

to provide the inaugural exhibition for their fair in early December. Nigel Benson decided on the subject "50

Years 0f British Glass 1924 - 1974" and curated the exhibition chosing mainly iconic pieces

that represented the influences, trends and changes in British glass production over a fifty year period, culminating

in the beginnings of the Studio Glass Movement.

The story

began with the 1924 British Empire Exhibition and the work produced by the Ysart's at John Moncrieff's under the name

of 'Monart' and went on to explore the art glass from Gray-stan and Nazeing from before WWII. The inception of 'art',

'designer', or 'progressive', cut glass with the only extant piece of Gordon Russell cut glass, made by James

Powell & Sons being on show.

Cut glass from before and after the WWII was fully represented with work by most

of the individual designers from the major British factories in Stourbridge, London and Edinburgh. This included pieces by

Paul Nash for the Harrods Exhibition of 1934, Keith Murray designs for both cut and blown glass and a rare swirl cut vase

designed by Clyne Farquharson and lead into the work of designers Tom Pitchford, David Hammond and Doreen Norgrove, for

Webb's; Deanne Meanley for S&W(Royal Brierley); Irene Stevens, David Smith, Len Green and David Queensberry, for

Webb Corbett; Ludwig Kny, Geoffrey Stuart, E A Pierce and John Luxton for Stuart & Sons; and William Wilson and Geoffrey

Baxter for Whitefriars, as well as a piece by Alexander Crichton and an unknown designer's work from Edinburgh

Crystal.

Apart from textured pieces for Whitefriars by Baxter, there was work from Peter Wheeler for the 'Studio

Range' produced by the company. This interlocked neatly into the beginnings of the Studio Glass Movement in England,

through the work and influence of Sam Herman and the opening of the Glasshouse in Neale's Yard, Covent Garden, London

where he started a studio glass co-operative with a number of his students from the Royal College of Art (RCA). Initially

Pauline Solven managed the shop and later Annette Meech; both had representative pieces in the show. The link between Sam

Herman and Michael Harris, through their meeting as lecturers at the RCA, and the effect of that meeting upon Harris

was illustrated through early pieces of his work at the Isle of Wight.

Thanks is due to the dealers

and collectors who were kind enough to loan items for the exhibition.

____________________________

"A Confusion of Cloudy and Combed "

An

invited exhibition held at the Cambridge Glass Fair in September 2010 concentrating on a

number of British glass manufacturers during the middle quarters of the 20th century who produced similar types

of wares which many collectors find confusing. The pieces in the exhibition were selected to defuse some of the problems associated

with identifying between the wares of Powell (Whitefriars), Nazeing, Gray-Stan, Monart, and Vasart with the addition of examples

sold by Elwell of Harlow.

These were the mainstream creators and sellers of ‘Cloudy’ coloured glass production during the period between

the wars running through to the mid 1960’s. Whilst there were other producers the exhibition was designed to look at

the mainstream makers that do still give collectors identification problems. Some,

as with Gray-Stan and Nazeing, were so similar that, should items be unmarked, it can be very difficult to decide which of

the two made it. Similarly, combed (or ‘Lattice’) wares, which are largely regarded as an extension of cloudy

production, were made by a number of these companies and, over the years, have also been confused.

There are few opportunities

to see examples by these companies directly compared, which make this a chance for collectors to contrast the differences,

and similarities, of cloudy and lattice wares from this period of British glass production. It was the first time that an

exhibition focused on cloudy and lattice glass produced in Britain during this period, and as such was well received.

|

|

|

Below are selected views of most of the exhibitions and groups of items from them

|

| A selection of Nazeing from the 1930's illustrating an aray of different patterns |

|

| A view across the 2003 exhibition held at Lowewood Museum |

"Nazeing Glass and its Origins"

|

| Vases illustrating the various uses of mitre cutting all designed by Irene Stevens |

|

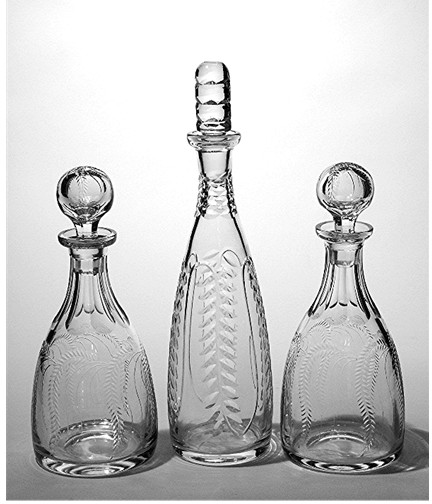

| Decanters for Webb Corbett designed by Irene Stevens |

"Art Deco to Post Modernism, A Legacy of British Art Deco Glass"

|

| A group of wavy mitre cut pieces by various companies |

|

| View across the exhibition held at the NEC in 2006 |

|

| Abstract and Sculptural cut items in the exhibition at the NEC |

"British 'Art' Cut Glass 1920-1970: A Fresh Look"

'Pride of Place'

Awaiting Photo

|

| Overview of both cabinets used for " A Confusion of Cloudy and Combed" |

Starting top left and finishing bottom right:

Single colour

cloudy; Two colour cloudy; Multi-colour cloudy; Lattice

|

|